THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE

Eritrea is a land of striking contrasts in terrain, climate and culture. Situated along the southeastern coast of the Red Sea in Northeast Africa, it is bounded on the east by Djibouti, on the south by Ethiopia and on the west by Sudan. The capital and largest city is Asmara. Its main ports are Massawa and Assab.

The Eritrean mainland stretches more than 1,000 kilometers along the Red Sea coast, one of the world’s busiest and most strategic shipping lanes. The temperate central plateau rises over two kilometers above sea level, while the scorched southeastern Danakil Depression is one of the lowest dryland points on earth. A lush Green Belt lies northeast of the capital. To the west are the fertile lowland Barka and Gash Plains.

The Eritrean mainland stretches more than 1,000 kilometers along the Red Sea coast, one of the world’s busiest and most strategic shipping lanes. The temperate central plateau rises over two kilometers above sea level, while the scorched southeastern Danakil Depression is one of the lowest dryland points on earth. A lush Green Belt lies northeast of the capital. To the west are the fertile lowland Barka and Gash Plains.

The Eritrean nation is made up of nine ethno-linguistic groups that embrace two of the world’s major religions, Islam and Christianity, and indigenous minority faiths. Eritrea celebrates this social and cultural diversity within an overarching commitment to national unity, and its people exhibit a quality of harmony rare in the world today.

GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES

Though small in size, Eritrea includes the varied topography and climate variations of an entire continent. It is said that one can experience three seasons here within two hours.

The three main geographical zones are the eastern slopes and coastal plains, the central highlands, and the western lowlands. Each has a distinctive physical and cultural character.

The low-lying coastal areas are mostly arid but get light winter rains and are crossed by the run-off from the summer rainy season in the highland plateau. The people living here year- round are mainly nomadic herders or seasonal farmers and artisanal fishers, though highlanders often bring their herds here during the winter. The slopes along the coastal escarpment and in the north and west have long been the focus of intensive cropping for domestic consumption and export. This area holds strong potential for future development.

The slopes along the coastal escarpment and in the north and west have long been the focus of intensive cropping for domestic consumption and export. This area holds strong potential for future development.

The temperate, mountainous interior is densely populated and extensively and intensively cultivated by sedentary farming communities. This is also where much of Eritrea’s light industry is situated.

The more thinly populated western lowlands receive run-off from the highlands and have underground water resources of their own, while the Gash region receives substantial summer rains. As such, the Gash-Barka region has considerable untapped agricultural potential.

Eritrea’s highest point is the peak of Amba Soira, in the Debub region. Its lowest point is the Kobar sink, located in the arid semi-desert of south-central Dankalia.

More than 350 islands dot the coastline, most of them concentrated in the Dahlak archipelago, east of Massawa. The largest of these, Dahlak Kebir, is 643 square kilometers with a population of about 1,500 in nine villages.

The country’s only year-round river is the Setit, in southwestern Eritrea, though many others flow from the plateau to the Red Sea and to Sudan during the summer rains, and the Gash, the Barka and the Anseba water large agricultural areas most of the year.

CLIMATE

The highest temperature in coastal areas occur from June to August and range from 25°C (80°F) to as high as 40-45°C (110°F). Temperatures here rarely fall below 18°C (64°F), though sea breezes provide some relief, especially on the islands. The rainy season along the northern Red Sea coast comes in December-February, when cloud cover is common. Rain is scarce along the southern Red Sea coast.

The highest temperature in coastal areas occur from June to August and range from 25°C (80°F) to as high as 40-45°C (110°F). Temperatures here rarely fall below 18°C (64°F), though sea breezes provide some relief, especially on the islands. The rainy season along the northern Red Sea coast comes in December-February, when cloud cover is common. Rain is scarce along the southern Red Sea coast.

In the central plateau, the highest temperatures occur in May, reaching 30°C (84°F). However, temperatures can fall as low as the freezing point at night during the winter months of December and January. The short rainy season in this area comes in April and May, and main one from late June to early September. Even then, it is normal for the sun to shine part of each day.

The hottest season in the western lowlands comes in April- June with temperatures reaching 40°C (100°F). December is the coldest month, as temperature drop to 10-12°C (50-55°F), but there are dramatic temperature differences here between day and night throughout the year. The rainy season is similar to that of the plateau, though lighter as less frequent outside the Gash region, but flooding from highland run-off is common in July and August.

NATURE

Plant Life: The eastern lowlands offer rolling acacia woodland, brushland and thicket, semi-desert vegetation and mangrove swamp. Kassod and flame trees line the roads to many coastal towns.

The central highlands are dominated by juniper and wild olive, as well as several species of acacia. East African laburnum native hops and eucalyptus are common along the roadsides and on steeply terraced hillsides.

The Semenawi Bahri slopes northeast of Asmara are the most thickly forested in Eritrea and have remnants of dense evergreen and tropical woodland. Southeast of Asmara, one finds majestic sycamores, such as that pictured on the five nakfa note.

The western slopes are dotted with baobab, toothbrush and tamarisk trees. This gives way to woodland savannah, brushland and thicket in the Barka and Gash Plains, which are broken up by dense groves of doum palm along the seasonal river beds.

Mammals and Reptiles: Eritrea was once home to a broad array of animal life, but war, colonial land seizures and the destruction of much of the forest cover drove many animals off. However, there has been resurgence in the wildlife population since independence, helped by strict prohibitions on hunting.

Common sightings today include vervet monkeys, baboon, gazelle, jackal, hare, fox, mongoose, wild cat, squirrel and warthog. Dikdiks and Dorcas gazelle are often seen along the coast. Less frequently observed but present are elephant, caracal, serval, oryx, crocodile, greater kudu and hartebeast. The endangered wild African ass can also be found, though rarely.

BIRDS: Eritrea hosts an abundance of birdlife with its varied habitats, some resident year-round, others seasonal. A total of 537 species have been identified, including the rare blue saw-wing.

The mostly uninhabited Dahlak Islands, with their rich feeding grounds, attract osprey, gulls, terns, boobies, ibis and white flamingo, among many other endemic and transient species.

The most forests of the Semenawi Bahri slopes are home to bush shrikes, francolins, sunbirds, tropical boubou and crimson turaco, as well as canaries, trogon, catbirds and hornbills, among scores of others. One small lake near Asmara is frequented by blue-winged goose, Roguet’s rail and the Abyssinian long claw.

Ostrich are increasingly common along the coast and in the western plains, as are African fir finch, scrub robin and spotted sand grouse, among others. Hundreds of species of birds also migrate through Eritrea in the autumn and spring.

Marine life: Marine ecosystems include coral reefs, sea-grass beds and mangrove forests. Patch coral extends around many of the islands and can be found in rich concentrations along the northern coastline.

Five species of marine turtle have been identified (green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead and Ridley), and several species of dolphin are common, especially around the Dahlak Islands. Whales have also been sighted, along with the endangered dugong, or seacow, which can be found in island waters and along the northern coast.

Nature Resources: Eritrea has many natural resources on the land and in the sea. The mix of climates supports a wide range of crops, including millet, sorghum, taff, wheat, barley, flax, cotton, coffee, papaya, citrus fruits, banana, mangos, beans and lentils, potatoes, various vegetables and fish and dairy products.

Livestock include sheep, goats, cattle, and camels. The Red Sea supports a wide range of edible fish, lobster, crab and shrimp, while coastal areas show promise for intensive saltwater fish and shrimp farming.

The geological mosaic of pre Cambrian, Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks holds extensive reserves of metallic, non-metallic and fossil minerals. Potentially profitable deposits of gold, copper, zinc, potash, iron ore and other minerals have been confirmed, while exploration continues offshore for oil and gas. There are also significant concentrations of high quality marble, granite, slate and limestone for construction purposes.

Protecting the Environment: Eritrea starts with a badly damaged environment in much of the interior, where large areas have been stripped of forest cover, wildlife and water resources. However, the country is endowed with more than 1,000 kilometers of pollution-free coastline and more than 350 islands not yet seriously affected by conflict or commerce. Even before independence, Eritreans acted to protect what remains and to promote as full a recovery as possible where damage was done.

First the Liberation Front and then the Government banned the hunting and trapping of wild animals and the cutting of live trees. After liberation, hundreds of kilometers of hillside terraces were planted. Large areas of the Red Sea coast were declared marine reserves, and spear-fishing and the collection of live coral were prohibited. Land was also identified for national parks.

Though pollution is not yet a significant problem, the Government has acceded to the UN convention on Biodiversity and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Reflecting these commitments, the Department of the Environment has prepared a National biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan and designed a Climate Change Project.

THE PEOPLE

Eritrea’s nation-building strategy is built upon a fundamental undertaking to unity in diversity. The government is firmly committed to policies of religious and cultural freedom and tolerates no discrimination or favoritism on any such basis The country’s most precious resource and that which holds the most promise for Eritrea’s future is its people. For this reason, the government invests heavily in health, social welfare, education and skill-development. It provides access to these services for all its citizens, regardless of their ethnic or religious background, their geographical location, their gender, age or other social category.

The country’s most precious resource and that which holds the most promise for Eritrea’s future is its people. For this reason, the government invests heavily in health, social welfare, education and skill-development. It provides access to these services for all its citizens, regardless of their ethnic or religious background, their geographical location, their gender, age or other social category.

There is no official language, though Tigrinya, Arabic and English predominate in commerce and national business. The use and development of all nine of Eritrea’s languages are encouraged at the local level, and children attend primary school through the fifth grade in their mother tongue.

THE NATIONALITIES

Eritrean Afars, also known as Dankils, live mainly along the southeastern sea coast and on the offshore islands in a highly-segmented, patrilineal society. Afars inhabit one of the least hospitable terrains on earth and are renowned for their prowess in battle. They have a long history of independent sultanates and strong warrior traditions. Many of their songs and much of their oral literature is built on this, and it is still common to see Afar men wearing the jile or curved knife. Today, most are herders, traders or artisanal fishers.

Pastoral Afar families typically live in large hemispherical houses of hides and woven mats stretched across a framework of wooden poles that can be carried by camel over long distances. In the few oases in Afar territory, the people cultivate maize and tobacco. Traders carry slabs of salt on their camels to the highlands from long-dried salt pans by the sea.

The Cushitic-speaking Bilen live in and around the city of Keren. Among them are Muslim and Christian (mostly Catholic) herders and farmers. Theirs is a traditional society organized into kinship groups. Bilen women are known for their brightly colored clothes, their gold, copper or silver nose rings, and henna tattoos that resemble diamond necklaces.

The Hedareb, also known as T’badwe, live in a wide arc stretching from western Barka across the northwestern valleys of the arid, volcanic Sahle region, where the liberation front had its fortified rear bases throughout much of the independence war. Their ancestral roots are among the Nilotic Beja peoples, whose territory stretches from Eritrea across northeastern Sudan to southern Egypt and who have lived along the sea coast for thousands of years. Their Muslim society is patrilineal.

Most Hedareb are semi-nomadic pastoralists. Many travel over long distances in search of pasture for their animals, which can include large camel herds as well as goats and sheep. The Hedareb are known as highly skilled camel drivers.

The Kunama live in southwestern Eritrea around the town of Barentu and close to the border with Ethiopia. Some are Christian, some Muslim, but many follow their own faith, centered around worship of the creator, Anna, and veneration of ancestral heroes. Their society is strongly egalitarian with distinctive matrilineal elements. Historically, most were hunters and farmers, tilling the soil with hand-held hoes to grow a variety of grains and vegetables. Today, they tend to be farmers and herders, whose cattle are also important sources of wealth and prestige.

The Kunama, thought to be among the aboriginal inhabitants of the region, were one of Eritrea’s largest nationalities until the late 1800s, when repeated assaults and slave-raiding by Tigrayan warlords sharply reduced their population and impoverished the society. Many of their dances are reenactments of historical events.

The Nara live in the western slopes and Barka plains. Like their neighbors, the Kunama, with whom they share some customs, the Nara are mainly sedentary farmers with a marked interest in cattle. However, their matrilineal family structure was transformed into a patrilineal one and their traditional religion forcibly supplanted by Islam-during the Egyptian occupation of their homelands in the 1850s.

The Rashaida are the country’s only ethnic Arabs. Mainly pastoralists and traders, the Rashaida migrated to northeast Africa in the 19th century from the Hejaz. They are Arabic-speaking Muslims, living along the northern coast and along the Sudan border in tightly-knit, patrilineal clans. Rahsaida women are noted for their red-and-black patterned dresses and their long heavy veils, often embroidered with silver, beads and seed pearls.

The Saho inhabit the coast and the hinterland south of Asmara and Massawa and the highlands as far inland as the Hazumo Valley. Most are Muslim. Some are seasonal farmers and herders, though a growing number are sedentary farmers living in the southeastern highlands. Among them are skilled beekeepers, widely known for their high quality honey. The Saho live in the patrilineal descent groups, each of which has a traditional warrior leader, the rezanto, who is accountable to an all-male public assembly.

The mostly Muslim Tigre people extend from the western lowlands across the northern mountains to the coastal plains. Most are herders and seasonal farmers, cultivating maize, durra (sorghum) and other cereals during the rainy season before moving with their herds and their families. Household goods, as well as sick or aging family members, are transported long distances by camel and donkey.

The Tigre have a rich oral literature of fairy tales, fables, riddles, poetry and stories of war and supernatural. They are also known for their singing and dancing, which is usually accompanied by a drum and a mesenko (a stringed instruments, plucked like a guitar). Theirs is a highly stratified society traditionally ruled by a hereditary village leader.

Most Tigrinya Speakers are sedentary farmers living in the densely populated central highlands of Maakel and Debub, though they are spread from this ancestral farmland over much of Eritrea today. The over-whelming majority are Orthodox Christians, though there is a small minority of Muslims, known as Jiberti, and there are significant minorities of Catholics and Protestants. Like all Eritreans, they are deeply attached to their land, but Tigrinya-speakers also make up a large population of urban traders and operators of small businesses, restaurants and other services throughout the country.

RELIGION & SOCIETY

Eritrean society is roughly divided among Muslims and Christians, with most Christians affiliated to the Orthodox (Coptic) Church. A small number of Eritreans practice traditional African religions.

Islam: Followers of the prophet Mohammed traveled to the Eritrean coast in 615 to establish relations with Adulite authorities and seek protection for the new faith, making this one of the earliest non-Arabian sites for the contact with Islam. Among the many important historical sites in Eritrea is the 500-year-old Sheikh Hanafi Mosque in Massawa.

Islam: Followers of the prophet Mohammed traveled to the Eritrean coast in 615 to establish relations with Adulite authorities and seek protection for the new faith, making this one of the earliest non-Arabian sites for the contact with Islam. Among the many important historical sites in Eritrea is the 500-year-old Sheikh Hanafi Mosque in Massawa.

Today, nearly all Eritrean Muslims are sunnis, the largest sect in Islam. Their highest religious authority is the Dar Al- Ifta, headquartered in Asmara. The ninth month of the Islamic calendar is Ramadan, a period of obligatory fasting in commemoration of Mohammed’s receipt of God’s revelation. A festive meal breaks the daily fast and inaugurates a night of feasting and celebration. Because the months of the lunar year revolve through the solar year, Ramadan falls at various seasons in different years.

Orthodox Christianity: Eritrea’s links to Christianity are thought to stretch back to the arrival of shipwrecked Syrian traders in the beginning of the 4th century. Over the years since, the Orthodox Church has served as critical repository of written records and iconic art. The Eritrean Orthodox Church separated from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church after Eritrea’s liberation and now functions as self-governing church in communion with the Coptic Church of Egypt.

Today, there are at least eighteen Orthodox monasteries in Eritrea. Many were built high atop mountain ridges or tucked into inaccessible places to protect against raids and attacks in the past. Among the oldest and most important are those at Debre Bizen (near Nefasit), Hamm (near Senafe) and Debre Sina (near Keren). The Debre bizen monastery houses more than 1,000 medieval manuscripts, including fine illuminated parchments bound in thick leather, cloth and wood.

Other faiths: Most Kunama practice their own traditional religion, centered around worship of the creator, Anna, and veneration of ancestral heroes. There are holy places associated with Anna but no institutional religious body, as the belief system is transmitted through elders of the community.

There are also significant Catholic and Protestant Christian minorities living mainly in or near urban centers in the highlands and the western slope areas.

RURAL LIFE

Approximately 60 percent of the population lives in rural areas, making their living from the land. But being a farmer or a herder is more than a job- it is a way of life. Rural Eritreans, whatever their regional or ethnic background, hold a deep and abiding relationship to the land, which both sustains and gives meaning to their existence. But it is a precarious one in the best of times.

Approximately 60 percent of the population lives in rural areas, making their living from the land. But being a farmer or a herder is more than a job- it is a way of life. Rural Eritreans, whatever their regional or ethnic background, hold a deep and abiding relationship to the land, which both sustains and gives meaning to their existence. But it is a precarious one in the best of times.

A comprehensive rural survey conducted by Leeds University found that less than two-thirds of those living in the countryside belong to the agricultural sector. Only a small minority, located mainly in the arid northern mountains and in the scorched coastal plains of southern Dankalia, live a purely nomadic existence.The great majority in the arid regions rely on cattle, camels, sheep and goats for food and income, supplementing this with sorghum or millet crops during years of normal rainfall. However, in drought years, they are forced to sell animals in exchange for grains and vegetables.

Because they move frequently, nomadic people are harder to reach with social services, such as health care or education. As a result, the poor in these areas suffer higher rates of maternal, infant and child mortality and lower life expectancies than other population groups. They are also less likely to be literate, especially women.

The overwhelming majority of rural dwellers in the central highlands support themselves by planting grain and vegetable crops. However, even full-time, settled farmers depend heavily on livestock for their economic existence- both for their role in the production process and as marketable commodities. Many rural highland families also derive income from non-farm activities trade, provision of services and the like and, like Eritreans throughout the country, from remittances.

URBAN LIFE

The first sizable towns of the modern area were the ports, which acted as gateways for regional trade and as administrative centers for a succession of colonial powers, from the Ottoman Turks to the Italians. Until the advent of the Italian era, most inland Eritrean towns were of modest size and served mainly as centers for local commerce. By the mid- 1930s, however, Asmara had swelled to a city of 120, 000 and other towns were rapidly growing around it Dekamare, Mendefera, Keren and others.

Some 40 percent of the populations now live in towns or cities. The largest of these is the capital, Asmara, with 450,000 residents. Its balmy, temperate climate, safe and spotless streets, remarkable architecture and cultural diversity make it one of the most livable cities on the continent.

Nearly all of Eritrea’s major towns and cities were originally built according to urban plans. The new government revised and developed these master plans in reconstructing and expanding many urban centers after liberation. Strict zoning standards have preserved the social and architectural character of the cities. This, coupled with sustained aid to poorer rural areas, has prevented the emergence of the slum belts and shanty towns that encircle many African cities.

CIVIL SOCIETY

The strength of any society is reflected in the depth and diversity of its self-organization. Eritrea’s stretches back hundreds of years and rests on highly sophisticated systems of customary law, giving it a firm foundation for internally generated growth development that can freely draw upon the experiences and achievements of others without jeopardizing either its integrity or its dynamism.

Women: Eritrean women played a central role in liberating the nation in 1991-and in defending it when it came under renewed attack in 1998- 2000. They are building it now.

Because of the important role women play in the society and economy, the government has sought to ensure their full and equal participation while eliminating the disadvantage many experience in marriage, separation, divorce, inheritance and access to property. Measures taken so far include:

* Reserving a minimum of 30 percent of the seats in the National Assembly for women

* Appointing women to high political positions, including ministerial positions.

* Promoting economic empowerment through education and skills training.

* Encouraging women’s employment in the civil service and acting to ensure equal treatment in promotion and job retention.

* Establishing institutional mechanisms (including educational) to address women’s issues in public policy and resource allocation.

Some 45 percent of households are headed by women, though, as a group, they are not poorer than households headed by men. This is partly because women have access to land and other productive assets and partly because they participate actively in the labor force (47 percent of which is comprised of women). Women are less likely to be literate and numerate than men, but this, too, is steadily changing.

The National Union of Eritrean Women is the main nongovernmental organization working with women throughout Eritrea and in the Diaspora. Founded in 1979 during the fight for independence, the NUEW became an autonomous, non-governmental organization in 1992. A decade later, it has more than 200,000 members. Among its main achievements are securing women’s participation in land reform policies, organizing literacy campaigns, building awareness of discrimination against women, operating a rural credit programme and lobbying government in women’s role within society.

Youth: Eritrean youth are at the center of the nation-building project. Boys and girls lead clean-up campaigns in their communities. Secondary school students spend summers working in agricultural programs and other development projects. Upon turning eighteen, young women and men participate in eighteen months of national service.

The National Union of Eritrean Youth and Students, with more than 170,000 members (over 40 percent of whom are women), is the largest national organization working with Eritrean youth at home and in the diaspora. It runs programs for girls’ education, vocational skills training, computer literacy, and leadership development, among many others. It also sponsors sports activities and clubs (first aid, aerobics, music, the arts, drama, and other areas), and it conducts national campaigns on FGM eradication, HIV/AIDS prevention, and other social issues.

NUEYS publishes its own newspaper in several Eritrean languages and it produces a one-hour radio program broadcast weekly throughout Eritrea. The union also organizes video programs and other forms of entertainment for the general public, and it runs literacy campaigns for youth in rural areas and for those displaced by the recent war.

Workers: Eritrea’s first trade union-the United Eritrean Workers for Independence was launched in 1952, the year the UN federated the country with Ethiopia. The organization was banned soon afterward, but its members continued to meet and to protest the denial of their rights as workers and as Eritreans. In 1958, during the largest of several mass demonstrations, Ethiopian troops opened fire, killing or wounding many workers. These events marked the effective end of legal trade union organizing for the next three decades.

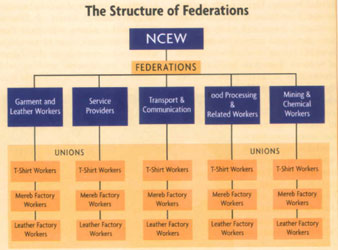

The EPLF organized the National Union of Eritrean Workers in 1979 to support the war for independence. The NUEW mobilized Eritrean workers abroad and it functioned clandestinely within Ethiopian-controlled town and cities in Eritrea. Between 1991 and 1993, the organization was transformed into a formal trade union structure, starting with a base union and proceeding to the establishment of five industrial federations. In September 1994 these unions launched the National Confederation of Eritrean Workers with 20,000 members.

By the end of the decade, with most of the industrial and semi-industrial workforce organized, the confederation began to look at such issues as: how to upgrade the skills of and con-scientize the workforce through a trade union education program; how to build shop floor democracy into the union’s structures through a shop steward training project; how to engage working women more actively in the unions through a confederation-wide Women’s Committee; and how to mobilize peasant producers into cooperatives and other new forms of self-organization.

Other Civic Organizations: In the years since liberation, many professional organizations have emerged anew or resurfaced with fresh vigor. Among them are associations of teachers, lawyers, nurses, medical doctors, engineers and architects, pharmacists and chemists. In 2001, the Asmara branch of the Eritrean Studies Association hosted the first international conference on Eritrean studies where more than 150 papers were presented by researchers and scholars from around the world.

Private charitable organizations are also thriving. Some are affiliated with religious institutions. Others, like Rotary International, function as local branches of non-religious international organizations. Still others, such as the Eritrean War Disabled Fighters Association, the Eritrean National Association for the Blind and the Family Reproductive Health Association, are the product of local initiatives designed to meet specific social needs.

The Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project works to conserve monuments, heritage sites, and the built environment, while also supporting living cultures. The Library and Information Studies Association helps communities across Eritrea to expand and develop public libraries. And numerous community-based sports federations, arts groups and cultural associations flourish at the national, regional and local levels.

With the growing human needs arising from the war-time emergencies of the late 1990s, several new NGOs also appeared. Among those providing training and other aid are Haben and Vision Eritrea. New organizations focused on the promotion of peace and human rights include Citizens for Peace in Eritrea and Rights Group.

THE DIASPORA

Since the early years of the independence war, diaspora communities in the Middle East, Europe, North America and as far as Australia have been integrated into Eritrea’s quest for self-determination and national viability. These communities were a critical source of moral and material support for the nation during the renewed war with Ethiopia in 1998-2000.

The first such communities were mainly comprised of students sent abroad on scholarships to the Middle East in the 1950s and to North America and Europe in the 1960s and 1970s. War and instability fed a steady exodus of others from this period onward- punctuated by large outflows when political repression was particularly intense in the urban centers-giving these communities a more complex, multi-layered character.

Students, workers and women organized themselves into popular associations to support the liberation struggle. Community centers developed to give people a reference point for one another, as well as a venue for sharing news, acculturating children, organizing cultural and social events and mobilizing resources for the homeland.

When war broke out with Ethiopia in 1998, overseas Eritreans responded swiftly and generously by undertaking new fundraising projects, making personal donations and purchasing interest-free bonds. Eritreans organized peaceful demonstrations in Europe, North America and Australia. A group in Washington organized the Eritrean Development Foundation, a registered NGO with chapters throughout the U.S., to assist Eritrean war victims and support reconstruction and development efforts.

Remittances from overseas Eritreans, coupled with local tourism by those who return for visits, are the country’s main source of foreign exchange. These remittances reached US$255 million in 1999 and US$200 million in 2000, as expatriates responded to the call for financial help during the conflict with Ethiopia. Private transfers are projected to increase to US$275 million in 2002 with the signing of the peace agreement with Ethiopia and the removal of exchange controls.