THE CULTURE

Elaborate rites and rituals have long been an important aspect of Eritrean culture. Cultural development was integral to the liberation struggle and has remained so since Eritrea’s independence, both as an expression of national identity and as a crucial arena in which the nation itself is constructed. During the independence war, it strengthened the nation’s determination, as it expressed the will for liberation. Today, it celebrates that achievement, as it manifests the country’s aspirations for peace and prosperity for all its citizens.

Each of the country’s nine nationalities has its own oral literary tradition, its music and dance, its architecture, its arts and crafts, and much more. Eritrea celebrates this rich heritage at all its major feasts and festivals, with performances and exhibits that showcase the unique contribution each makes to the whole.

FESTIVALS & HOLIDAYS

A National Holidays Coordinating Committee, with subcommittees in all six regions and in the diaspora, plans and manages celebrations, commemorations and festivals throughout the country each year. The main ones are National Day 24 May), Martyrs Day (20 June) and the annual Eritrea (August), but there are many others.

A National Holidays Coordinating Committee, with subcommittees in all six regions and in the diaspora, plans and manages celebrations, commemorations and festivals throughout the country each year. The main ones are National Day 24 May), Martyrs Day (20 June) and the annual Eritrea (August), but there are many others.

Regional festivals, youth fairs, and cultural competitions are held throughout the country, organized by municipalities, local administrations and nongovernmental organizations, such as the unions of women and youth. The media play a major role in promoting them, with extensive coverage on radio, TV, and in the newspapers.

The Annual Eritrea Festivals held in Asmara and attracting nearly 600,000 people is the cultural event of the year. The festival features songs, dances and dramatic performances from all nine nationalities and much more in a continuous exposition that runs for ten days. Among the featured events and exhibits are models of traditional homes, arts and crafts shows, traditional foods and refreshments, rites and ceremonies, special exhibitions of artistic and scientific merit, and highly competitive contests. Similar festivals are organized by diaspora communities in the Middle East, Europe, North America and Australia

The Raimoc Awards, whose name derives from Hedareb word for the beauty and grace in the long neck of an antelope, are presented to the individuals and groups in Eritrea who most excel at literature, music, painting, drama, traditional folklore and other categories. The annual prizes total as much as 400,000 nakfa, and the contests are fiercely contested, from regional competitions that narrow the field to the finals held in Asmara in August.

THE COFFEE CEREMONY

Strong, aromatic coffee is often drunk in Eritrea in an elaborate ritual that brings families and their guests together in an hour-long ceremony at the close of a long work day. It is usually served in thimble-size, handleless cups and accompanied by trays of fresh popcorn and raisins, hambesha (bread) and other local specialties.

Strong, aromatic coffee is often drunk in Eritrea in an elaborate ritual that brings families and their guests together in an hour-long ceremony at the close of a long work day. It is usually served in thimble-size, handleless cups and accompanied by trays of fresh popcorn and raisins, hambesha (bread) and other local specialties.

Typically, a woman of the household scatters strands of fresh grass on the floor to provide the freshness of the outdoors, as she roasts green coffee beans over charcoal fire, shaking them frequently to prevent burning. Once they are blackened and ready for grinding, she wafts the fragrance under the noses of the celebrants and then pounds the beans into a powder with a wooden mortar and pestle.

The coffee is repeatedly heated to a boil in a round clay pot with a thin, stem-like neck, as frankincense burns nearby. Participants are expected to partake of at least three rounds of the full-boiled brew, between which tall glasses of the local beer, sewa, are often served.

THE ARTS

Architecture:Eritrea’s major cities exhibit strong colonial influences, as with Asmara’s Florentine and Art Deco styles and Massawa’s Turkish and Egyptian styles. However, its smaller towns and villages each have a character of their own, drawn from the cultural heritage of the nationalities living there.

Asmara has a profusion of well-preserved office buildings, hotels, cinemas, residences and service centers that reflect architectural styles as varied as Internationalist, Cubist, Expressionist, Functionalist, Futurist, Rationalist and Neoclassical. There are massive stepped towers and brick string-courses, Doric columns and hand-crafted wrought-iron gates, curved corner entrances and porthole windows, rusin-urb gardens and elegant villas with marble staircases, louvered shutters, curving balustrades and shay porticos.

Asmara also houses the region’s first synagogue, built in 1905, in the Neoclassical style; the Kulafah Al Rashindin (Great Mosque), built in 1938 and combining Rationalist, classical and Islamic styles; and a towering Catholic cathedral, consecrated in 1923, that is said to be one of the finest Lombard-Romanesque-style churches outside Italy

Massawa is noted for its covered passageways and coral-block houses, with their trellises balconies and finely carved wooden doors and shutters. In the heart of Massawa Islands is the 500 year old Sheikh Hanafi Mosque. A short walk from there, on nearby Taulud Island, is the soon-to-be-restored 16th century palace of the Turkish Osdemir Pasha that overlooks the busy harbor, where brightly-colored, hand-crafted dhows furl their classic triangular lateen sails and offload exotic cargoes.

In the cooler uplands, most rural Tigrinya-speaking families live in flat-roofed, rectangular houses, hidmo, with dry-stone exterior walls and thick interior wooden pillars that define separate spaces for sleeping, food preparation and the stabling of farm animals. In the slope areas and the hot, arid lowlands, most people live in circular single-room dwellings, constructed out of sun-dried adobe, dried sticks or grass and crowned with conical thatched roofs.

Music & Dance: Every nationality in Eritrea has its musical traditions and its distinctive dances, usually performed to the rhythms of intricate, locally-produced instruments. These may include single-or multi-stringed krars and watas, flutes of varying lengths, drums, rattles and tambourines, sometimes played together with modern amplified instruments. Many mark major events in life, such as birth and marriage, or celebrate important religious or community festivals. There is also a growing popular music culture in the major urban centers, which draws on and reinterprets traditional themes.

Literature: The nation’s rich oral literature tradition ranges across all nine nationalities and includes a wealth of poetry and proverbs, songs and chants, folk tales, histories and legends. Until recently, most of Eritrea’s written literature was religiously based. Since independence, however, new works of poetry, drama, narrative fiction and memoir have appeared.

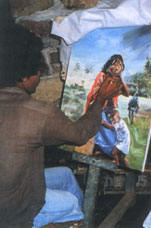

Painting:The most common traditional painting, usually done on skin, parchment or event canvas, depict religious themes and fables or abstract designs and shapes in board forms. Most church walls are painted with colorful and dramatic murals. More modern styles developed during the liberation struggle, varying from harsh realism to highly symbolic renderings of social and political themes. Portraiture and landscape art have also become common.

Theatre: Traditionally, drama was used to celebrate religious festivals. It usually involved music, singing, dancing and acting. During the liberation struggle, short skits and full-length plays depicted historical events and cultural practices, interpreted political and social issues, and entertained and amused large audiences throughout the country. Since independence, new works, some carefully scripted, others more improvisational have begun to appear. Alemeseged Tesfai’s The Other War has been performed in Eritrea and Europe and appeared in an English anthology of African plays.

CRAFTS

Pottery: Ceramic work constitutes one of Eritrea’s oldest crafts, for pottery products grace nearly every household. Slender-necked pots, djebena, are part of the classic Eritrean coffee ceremony, just as clay pots, tsahli, are integral to the spicy chicken stews served on most festive occasions. Also ubiquitous in rural households are the large ceramic water pots, known as utro, and the brightly-painted irregularly-shaped incense holders. Today, in the urban centers, one can also find handmade ceramic flower vases, candle holders, ashtrays and other household objects.

Pottery: Ceramic work constitutes one of Eritrea’s oldest crafts, for pottery products grace nearly every household. Slender-necked pots, djebena, are part of the classic Eritrean coffee ceremony, just as clay pots, tsahli, are integral to the spicy chicken stews served on most festive occasions. Also ubiquitous in rural households are the large ceramic water pots, known as utro, and the brightly-painted irregularly-shaped incense holders. Today, in the urban centers, one can also find handmade ceramic flower vases, candle holders, ashtrays and other household objects.

Weaving & Basket-making: Much of Eritrean basketwork derives from its uses in the preparation, serving and storage of food-from breakfast plates and bread baskets to lunch boxes taken by farmers and herders to the fields but there is a growing trade in basketry intended solely for decoration, such as colorful table mats, wall hangings and centerpieces.

Jewelry: Finelyworked gold and silver earrings, necklaces, bracelets and rings are commonly given to women on their wedding day. While precious metals are rarer in the countryside, many rural women have jewelry strung together from beads and worn around their heads, necks, wrists and ankles. Among the other highly-prized traditional metalwork are Orthodox crosses made of silver and brass

Leather work: Traditional leather-work is often decorated with beads and cowry shells, though locally tanned leather is often used to cover handmade stools, seats, baskets and drums. There is also a growing trade in fashionable handbags, shoes, belts and coat. As Eritrea has banned wildlife products, all leather products are derived from domesticated animals.

Wood-carving: Many Eritrean carvers use the pale wood from the olive tree to produce picture-frames, bowls, salt and pepper shakers, candle holders, small shields and other household items, some functional, some purely decorative. Colorful porcupine quills are often worked into the design. Other local wood is used to make rough-hewn chairs and tables, low-rise stools, camel saddles and T-shaped pillows intended to keep the head away from potential snake, scorpion or spider bites.

Museums & Libraries: The National Museum is headquartered in Asmara, but it is in the process of establishing a network of regional centers. It includes exhibits on all the ethnic groups of Eritrea, the country’s main archeological sites and the 30 year independence war.

The Research and Documentation Center (RCD) houses the archives from the liberation war and is a repository for many other historical documents, oral and written histories, photographs, maps, charts and other visual records. It is negotiating the return of valuable lost documents and artifacts from individuals, governments and other institutions, and it is collecting recently published works of historical and artistic merit. In the future, the RCD will develop into an autonomous National Library and Archives.

ART & CULTURE ORGANIZATION

The Cultural Heritage Project (recently renamed the Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project) seeks to conserve monuments and heritage sites, conserve the built environment and support living cultures. It works with the National Museum, the University of Asmara and various community based organizations throughout the country to heighten public awareness of Eritrea’s exceedingly rich cultural resources, ancient and modern, and to help manage this legacy.

Among the many new organizations nurturing and promoting modern art music are the Mrara Art Association and the Asmara Art Club. The Eritrean Library Association is active in developing and stocking public libraries in all regions of the country.

International cultural organizations and agencies represented in Eritrea include the British Council, Alliance Francais, the Eritro-German Club, Casa Degli Italiani, the Pavoni Library and the American Cultural Center.

THE MEDIA

The first printing press was introduced into Eritrea in 1866 by European missionaries, but the first indigenous Eritrean newspaper did not appear until 1947, when British military administrators permitted their establishment. These publications were abruptly curtailed by Ethiopian authorities shortly after the imposition of UN-sponsored Federation in 1952. Nationalist media did not reappear until the start of armed resistance in the 1960s and 1970s.

The first printing press was introduced into Eritrea in 1866 by European missionaries, but the first indigenous Eritrean newspaper did not appear until 1947, when British military administrators permitted their establishment. These publications were abruptly curtailed by Ethiopian authorities shortly after the imposition of UN-sponsored Federation in 1952. Nationalist media did not reappear until the start of armed resistance in the 1960s and 1970s.

By the early 1980s, the EPLF was producing daily radio broadcasts in six languages and an average of eight periodicals and nine film documentaries each year. By the end of the liberation war, EPLF crews had produced sixty four films depicting the armed struggle, the condition of war prisoners and political rallies, as well as public health work, traditional songs and dances and many other social and cultural themes.

In the immediate postwar years, all media were state-owned and operated, most of them extensions of the print and broadcast media developed by the liberation front. However, publications soon began to come out regularly from civil society organizations, charitable societies and other nongovernmental sources, and in 1996, with the promulgation of a national press code, privately owned newspapers appeared. In 2000, Eritrea went onto the internet, with four local service-providers that are available in most of the country’s major towns and cities.

Eritrea’s main objectives in this field are to: develop free, responsible and credible mass media; to promote the democratization process and strengthen national unity; to provide the public with news and timely information, as well as entertainment and enlightenment; to enhance cultural values and traditions; to enhance public debate and discussion.

The Press: The Ministry of Information publishes three newspapers: the Tigrinya daily Hadas Eritrea, with circulation of more than 20,000; the Arabic daily Eritrea Al-Hadisa, with a circulation in excess of 4,000; and the English-language weekly Eritrea Profile, with a circulation of about 4,000.

Since the adoption of a national press code in 1996, several private papers have appeared. Private magazines and periodicals aimed at specialized audiences also appear at irregular intervals, as do publications from regional administrations, charitable groups, religious associations and others.

Radio: Dimtsi Hafsh (Voice of the Broad Masses), begun under the Liberation Front in 1979, is Eritrea’s only national radio service. The high illiteracy rate among Eritreans, particularly in rural areas, makes this the most effective medium to educate and inform the general public. State-owned and operated, it broadcasts from Asmara, though its correspondents are stationed throughout the country. With a transmission power of 100 kilowatts, Dimtsi Hafash covers all of Eritrea and much of the surrounding region of northeast Africa.

Programming originates in the Tigrinya, Arabic, Tigre, Kunama, Saho, Afar, Bilen, Hedareb, Nara, Amharic and Oromifa language and covers a wide range of subjects targeted at general and specific audiences. Children and youth, for example, broadcast their own shows each week.

Television: The state-owned and operated EriTV began broadcasting from Asmara in 1993 with a one-kilowatt signal and relay stations in key positions, EriTV’s broadcast reach most of the southern, eastern and northern parts of the country, though Eritrea’s mountainous topography has hindered signals from covering the whole nation.

EriTV programs in four languages (Tigrinya, Tigre, Arabic and English) with specialized desks for news and current affairs, politics, and development, entertainment and sport and culture and the arts. Educational programs range from public health issues, innovative agricultural practices and environmental issues to household economy and the special needs of children.

EriNA: The government-operated Eritrean New Agency collects local, regional and international news and information and distributes it to the newspapers, the radio and the television. EriNA correspondents in all six regions of the country communicate with the head office through telephone, two-way radio and computerized radio transmission.